A tertiary line of external evidence known as patristics, is a factor of consideration. By exploring what Church and Apostolic Fathers may or not have commented on PA, we may weigh the corresponding appropriate witnesses with text-critical methodology. To commence, In his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius of Caeseara preserves a citation of Papias of Hierapolis, a second-century Greek Apostolic Father and Bishop of Hierapolis, who states,

“Matthew put together the oracles [of the Lord] in the Hebrew language, and each one interpreted them as best he could. [The same person uses proofs from the First Epistle of John, and from the Epistle of Peter in like manner. And he also gives another story of a woman who was accused of many sins before the Lord, which is to be found in the Gospel according to the Hebrews.” (PAPIAS, Fragments VI)

At first glance, Papias may seem to referring to the narrative of PA in the Gospel of John, however, this citation is dubious for several reasons: 1) The general obscurity and lack of narrative detail, doesn't provide enough data to hastefully assert this quotation to be referring to PA. However, even examning the content of the narration provided, we can already isolate underlying contradictions in detail, for example, the woman being accused of “many sins” before her Lord. If we read PA in GJohn, a woman is accused of not “many sins” but only adultery, hence the label “adulteress” or “adulterae”. This precise detail of "many sins'' is unique to this citation of Papias of Hierapolis and is not reflected by any other patristic witness of PA in the UBS apparatus. The textual patristic tradition generally adduce a woman that was accused of "the sin" (αμαρτία) which is loosely agreed to have been some form of adultery. Another important contention is that a wide range of scholars such as Knust and Wasserman argue that in this citation, Eusebius of Caesarea recognizes and attributes Papias’ narration to the Gospel according to the Hebrews, an early Jewish-Christian Matthean non-canonical text that was canon among second century heretical groups such as Ebionites and Nazarenes and is not related to the Gospel of John. Nevertheless, we cannot even be certain that the Gospel according to the Hebrews attests the same detail of “many sins” when the written patristic tradition uniformly attests αμαρτία (“the sin”) or adultery and the Gospel according to the Hebrews is lost source-material. Even the 1st Greek MS to include PA, Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, includes the varie lectiones of “sin” (αμαρτία) instead of adultery (μοιχεία) along with 1071. The question that follows from here, is what is the source tradition of Papias’ narration? Ehrman and Kok suggest that Papias has been shown to favour quoting from the oral tradition that he has learned from his "elders" who are referred to as companions of the disciples of Jesus by Eusebius. Even in the context of the chapter of the narration, Eusebius is relating some of the stories that Papias had learned from the ‘elders.’ Papias is said to prefer the ‘living voice’ of oral tradition (i.e. his living authorities) to the ‘books’ about Jesus available to him (E.H. III, 39, 4). Among the stories he learned from the elders are the accounts of how Mark and Matthew came to write their Gospels. Papias’ preference of living tradition to Christian writings suggests that his story of Jesus and the adulteress derived from the reports of the ‘elders’ rather than from a written text or tradition. This seems to be the most likely origin of Papias’ narration. Thus, we have traversed two primary points: 1) Papias is quoting a somewhat full narration of a woman who was accused of many sins before the Lord, and 2) Papias is not quoting from a early textual tradition but the oral tradition of the Elders. With such arguments considered, the claim that Papias’ is referencing PA found in the Gospel of John becomes inadmissible. Not only do we clearly observe conflicting narrative details and biblical placements, but also a divergence of source tradition. Those who take Papias’ narration as an faithful instantiation of the second-century oral tradition of Papias' authorties, must concede that that PA relayed by Papias of Hierapolis separated from second-century oral tradition, assuming new narrative details and biblical placements, once of which would be GJohn. All in all, Papias cannot be said to corroborate the PA in GJohn.

Aside from Papias of Hierapolis, another patristic witness that seems to quote PA is the Didascalia Apostolorum, a third-century church manual of the Syrian provenance preserved in the Apostolic Constitutions, dated to the end of the fourth century. It reads:

“But if you do not receive the one who repents, because you are without mercy, you will sin against the Lord God. For you do not obey our Savior and our God, to do as even He did with her who had sinned, whom the elders placed before Him, leaving the judgement in His hands, and departed. But He, the searcher of hearts, asked her and said to her, “Have the elders condemned you, my daughter?” She said to him, “No, Lord.” And he said to her, “Go, neither do I condemn you.” (2.24.6)

To conclude our analysis of the relevant patristic citations, in the first three centuries of the Christian era, there is not a single patristic witness that mentions PA but subsequent several Fathers that 1) present primitive forms that are bereft of narrative detail and adduce bizzare biblical placment 2) such primitive forms do not even loosley agree with PA in GJohn and contradict with other primitve forms of PA known to us 3) We have other early fathers such as Origen, Tertuillian and Cyprian of Carthage that adduce no awareness of any PA-like narrative.

As we have covered, the citations from the patristic authorities all bear some level of dubiety, and cannot count as direct witnesses of PA in GJohn, but present a new perspective on the timeline: primitive versions of an PA-like narrative. However, we find that several early Fathers of varying geographical areas that are perspicuous about the silence of PA. We begin with Tertullian, a second-third century Latin Father that, suprisingly, does not allude to PA. We know this from his public treatise, De Pudicitia, of which Tertullian has become displeased with the complacent willingness of his fellow members of the Church to forgive anything, evinced especially by an edict of a bishop, perhaps Agrippinus of Carthage who allowed adultery and fornication. Adultery is one of the principal themes of the treatise, which yields heavy prior probability for the mention of PA, had the narrative been truly available in GJohn and Tertullian were aware of it. Had this been true, we could certainly expect PA to have been mentioned in his public treatise, but rather we have no trace of such a mention. This, along with the fact that virtually all Coptic versions we’ve covered earlier do not adduce PA is sufficient to conclude Tertullian did not know the passage. Nextly, Cyprian of Carthage (258), a contemporary of Tertuillian who lived in the same area of Carthage, is silent on the passage Similar to Tertullian, wrote about adultery as a mortal sin, but also mentions the possibility of repentance and resumption: In letter 51, Cyprian is citing John 5:14 and 2 Corinthians 12:21:

"And, indeed, among our predecessors, some of the bishops here in our province thought that peace was not to be granted to adulterers, and wholly closed the gate of repentance against adultery. Still they did not withdraw from the assembly of their co-bishops, nor break the unity of the Catholic Church by the persistency of their severity or censure; so that, because by some peace was granted to adulterers, he who did not grant it should be separated from the Church. While the bond of concord remains, and the undivided sacrament of the Catholic Church endures, every bishop disposes and directs his own acts, and will have to give an account of his purposes to the Lord ... Or if he appoints himself a searcher and judge of the heart and reins, let him in all cases judge equally. And as he knows that it is written, Behold, you are made whole; sin no more, lest a worse thing happen unto you, [Jo 5:14] let him separate the fraudulent and adulterers from his side and from his company, since the case of an adulterer is by far both graver and worse than that of one who has taken a certificate, because the latter has sinned by necessity, the former by free will ... And yet to these persons themselves repentance is granted, and the hope of lamenting and atoning is left, according to the saying of the same apostle: I fear lest, when I come to you, I shall bewail many of those who have sinned already, and have not repented of the uncleanness, and fornication, and lasciviousness which they have committed. [2Co 12:21] (To Antonianus: About Cornelius and Novatian, Epistle 51:21, 26)

Contrary to Tertullian’s public treatise, Cyprian’s letter is more interconnected with the theme of adultery, as not only does he claim adultery to be a mortal sin, but argues that the gates of repentance are open for those who fall into adultery. There is not a narrative more evokeful of the themes of adultery and repentance then PA of John 7. And yet, we find that the Cyprian of Carthage does not reminisce about the story of Jesus of Nazareth forgiving the adulterous woman.

Nextly, perhaps the esteemed patristic scholars of this time period, we have Origen of Alexandria, who is more direct and explicit in John 7:53:8-11. In his “Commentary of John'', Origen moves his discussion from the end of John 7 through John 8, without mentioning the story of the adulteress once. This is telling, considering that Origen has not only used GJohn frequently in his patristic exegesis, but also the Gospel according to the Hebrews as a more spurious source, which according to Papias of Hierapolis’ narration, included an primitive form of the Pericope de Adulterae. Yet from neither GJohn, nor the Gospel according to the Hebrews, does Origen mention PA. One also must consider whether or not, Origen's silence of PA provides some dubiety to Eusebius' attribution of primitive PA to the Gospel according to the Hebrews or Origen's source-material.

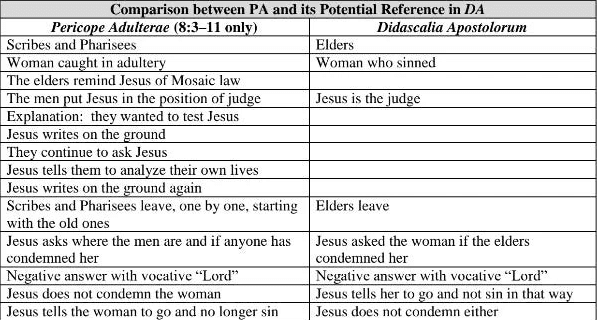

Similar to the narration from Papis of Hierapolis, the quotation lacks narrative details found in later Western patristic exegesis and preserved in GJohn. As seen in the figure, the interlocutors are identified as “elders” rather than as scribes, Pharisees, priests, or Jews; these elders brought the woman before Jesus for judgement and departed before judgement was given; there is no mention of Jesus writing on the ground or of the intended punishment; the woman’s sin remains unspecified, and finally the last two narrative lines are reversed. Also note that the designation “elders” is unique to the Didascalia Apostolorum and is not attested in any other version of the Pericope de Adulterae. Hence the conclusion for the Didascalia Apostolorum is that of Papias. Both Papias of Hierapolis and the Didiscalia Apostolorum represent potentially primitive forms of PA, do not cohere with PA in GJohn and with each other.

We now turn to a witnesses, which scholarship has studied more recently. Didymus the Blind, a fourth-century Alexandrian teacher and theologian, wrote a series of extensive biblical commentaries to his local Alexandrian Christians. In Didymus the Blind’s Commentary of Ecclesiastes 7.21–22, he states,

“We find, therefore, in certain gospels [the following story]: A woman, it says, was condemned by the Jews for a sin, and was being taken to be stoned in the place where that was customary to happen. The Saviour, when he saw her and observed that they were ready to stone her, said to those who were about to cast stones, “He who has not sinned, let that one take a stone and cast it.” If anyone is conscious in himself not to have sinned, let him take a stone and smite her. And no one dared. Since they knew in themselves and perceived that they were also liable for some things, they did not dare to strike her.” (223.10-13)

Didymus reports that he found the pericope adulterae in “certain gospels”. The meaning of this phrase is a subject of some disputation in scholarship. The editors of the Commentary of Ecclesiastes fragments conclude that Didymus must have found the story in some, but not all of his copies of John. Bart D. Ehrman famously proposes that Didymus the Blind is quoting from the Gospel according to the Hebrews, which has been documented prolifically by Origen of Alexandria to have been circulating around Alexandria during the fourth-century. Another recent commentator, Dieter Lührmann contends that Didymus must be referring to apocryphal gospels, probably the Gospel of the Hebrews. Another opinion supposes that if “certain gospels” refers to only some gospel-manuscripts of John during the fourth-century, this necessarily implcates the Pericope de Adulterae’s non-canonical placement in John. However, if Didymus refers to the Gospel according to the Hebrews, or an apocryphal gospel, then the story of the adulteress is of apocryphal origin. Nevertheless, wherever he found it, Didymu's narrative-form of PA is different from what we have seen from other early versions of PA. According to Didymus, the woman was accused by “Jews,” not by elders or scribes. The designation ‘Jews’ is strange, as not only are the Pharisees denoted, but also the Sadducces, Essenes and other Jewish denominations around the time of Jesus of Nazareth. The Jews were “liable for some things” and as such, they were unable to carry out the stoning once detained by Jesus. In this version, Jesus strangely intervened uninvited; he was not asked for his opinion, but witnessed the scene as an outsider. Still, his authority was accepted by the woman’s accusers, who “did not dare to strike her '' once their sin had been pointed out. However, the woman’s sin is still unspecified, and Jesus is not said to have written on the ground.

External Evidence: "Against" Patristics

Conclusion

The Pericope de Adulterae, otherwise known as John 7:53-8:11 is the passage about Jesus of Nazareth's encounter with a woman who is condemned for some sin to which Jesus forgives and excuses her transgression. The ambiguous quiddity of such a summary is not deliberate, but solely instantiates the unreliable textual character. For indeed, numerous crucial details, such as who condemned the woman, the woman’s transgression, the dialogue between whoever brought forth the charge of transgression and Jesus of Nazareth, Jesus writing on the ground and other narrative details have been determined to “textually insecure” and therefore must be discarded when formulating an accurate and autographical summary of the pericope de adulterae. Even more ironic, however, is including the words, “autographical” and “pericope de adulterae” in the same sentence, as leading scholars including Daniel Wallace, Bart D. Ehrman, Bruce Metzger and the bulk of New Testament scholarship contend that John 7:53-8:11, is “the clearest example of New Testament corruption.” We will provide a thorough overview as to why this scholarly consensus is certain and uncontested.